[:en]Amy Iadarola: How did you start working with dancers in your practice, Rebecca?

Rebecca Carli: Well, I have worked with various types of dancers since the beginning of my Rolf Movement Integration and Rolfing Structural Integration (SI) career – twenty-eight years ago now. Likely, dancers are drawn to my practice because I have college degrees in dance, specialize in concerns specific to dancers, and have been connected with various dance communities. This has made a satisfying bridge from my dance life to my Rolfing life. In fact, I originally sought out Rolfing SI because of dance injuries. A month before graduating from my MFA program, a bone scan revealed stress fractures in both tibias. An orthopedist began counting them on the films; when he got to forty, he said, “I am going to stop counting here, and you are going to stop dancing now.” This solution for dance injuries was common before wide acceptance of the field of dance medicine. Luckily, my advisor at the university was familiar with Rolfing SI and sent me in a direction that was beneficial to my tibias, and perhaps more importantly, unfolded a new path for my passion for movement.

AI: I know you work with a lot of modern dancers, Rebecca, but do they make up the majority of the dance population you see, or do you work with other kinds of dancers as well? And do your clients’ issues and concerns vary according to the type of dance they engage in?

RC: All types of dancers – ballet, modern, hip hop, ballroom, contact improvisation, and others – seem to want one thing from their Rolfing experience: to dance better. This means different things to each individual dancer, relevant to [his/her] style of dance. Ballerinas may want to work en pointe with more ease, modern dancers may want to have more flow in transitioning to and from the ground, ballroom dancers may want more quickness and directness in foot work, hip hop dancers may be concerned with specificity in their expression of rhythm, contact improvisers may be interested in heightening their somatic listening skills, and so on. The foundational tenet of Rolfing SI – to increase ease and efficiency in a person’s relationship with gravity – will have a positive impact on a dancer’s ability to dance. When a dancer’s relationship with gravity is brought to consciousness and integrates into [his/her] training, resulting shifts in alignment and awareness will allow more optimal function. Muscles that may be overly involved in posture are now available for movement, aspects of coordination are refined, and clarity in expressivity is increased. A primary concern for a dancer, like any person, is to not fall down (unless he/she chooses to do so), so efficiency and ease in negotiating gravity is foundational.

Having said that, some of the conventions of each dance style may, at first, seem to run counter to most of the ideas inherent in Rolfing philosophy – such as pointe shoes and turnout for the ballerina, four-inch heels for the ballroom dancer, stomping and fixed arms for Irish step dancing, lifting people who outweigh you in contact improvisation, and so on. The goal of the dancer in your office may seem to go against what you know to be healthy and wise for the human body.

It’s important to note that we are talking about stylized forms of dance with specific techniques and principles dictating movement vocabulary, not natural or tribal dance based in cultural and spiritual traditions, such as that performed by the Maasai, Odisha, or Hopi, or even just freedom of expression through dancing that arises within us in response to spirit, rhythm, or community – otherwise known as the ‘boogie’.

AI: So how do you navigate this – realizing the goals of Rolfing SI while at the same time helping your client excel in his/her stylized dance form?

Figure 1 Marie Taglioni in Zéphire et Flore by Chalon, circa 1831

RC: If you want to work with dancers, you find a way to marry the two. You understand that this person’s passion and much of her spirit for life springs from this art and, for better or worse, she will continue to push limits. Dancers love to dance; if not, they would stop – the necessary output of energy, fortitude, and time rarely, if ever, equals the financial gain. They love what they receive from the act of dancing, and most of their identity comes from being a dancer. There are some ways of understanding a dancer’s concerns that make the marriage easier and our work together more productive. Most of my understanding and incorporation of these ideas in my practice comes from insights that I have gained through my ongoing studies with Hubert Godard.1

AI: Can you give us an example of how you marry the goals of Rolfing SI with those of dancers, perhaps by talking about ballerinas and their pointe shoes?

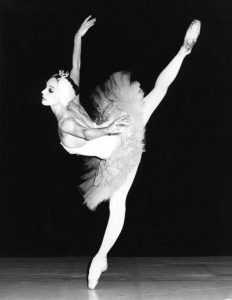

RC: Ever since Marie Taglioni (see Figure 1) performed La Sylphide en pointe [1832], classical ballet has been defined by the wearing of pointe shoes. Incidentally, it is said that Taglioni’s fans loved her so much that they cooked her pointe shoes and ate them in a sauce! The ergonomic nightmare of the pointe shoe came about because ballet attained widespread popularity during the Romantic era, when ballet choreography focused on the theme of unattainable love: mortal men smitten by supernatural women – sylphs, wili, water nymphs, and fairies. The pointe shoe was the perfect tool to create the illusion of extreme lightness, not bound by this earth. Ballet technique then developed to use the form and function of the pointe shoe, becoming ever more challenging. Ballerinas are now expected to not only dance on top of the pointe but also to perform many complex movements in demi-pointe [on the ball of the foot] or flat while wearing pointe shoes. The design and construction of pointe shoes has improved with newer materials, but they fall far short of supporting a Rolfer’s ideals of weight evenly distributed across the whole foot, toes free to spread, smooth transition across the transverse arch, and so forth. In fact, when a ballerina is en pointe, she may be supporting ten times her body weight on the tip of the distal phalanx of her first metatarsal.

It is said that 80% of ballerinas experience ankle injury while wearing pointe shoes, primarily because they either ‘sickle’ [invert] or ‘wing’ [overly evert] their forefoot when en pointe, sending uneven forces into the corresponding ankle structures. Even a small degree of sickling can create problems because this means that the ballerina is not effectively finding a strong connection between her gravity center and the balance required for her weight to transition strongly through her first metatarsal. While a small amount of eversion is necessary to stabilize the subtalar joint for balance en pointe, too much means that the dancer is over-pronating her foot and her weight will fall medial to the first metatarsal to balance. Either way, the ankle’s soft-tissue structures are in jeopardy.

A benefit that Rolfing SI can contribute is to create clarity and facilitate adequate functioning of the medial line in balance with the lateral line to organize the leg. Beyond working with relevant structures and patterns of coordination, an equally important task is to clarify a dancer’s perception in the activation of her medial line. Ballet dancers are perceptually oriented to ‘turnout’ – externally rotated femurs – as a foundation for the majority of movement. They rarely work in parallel, especially en pointe. This can create imbalance between mobility and strength in the inward and outward rotators of the hip joint and the adductors/abductors of the entire leg. By initiating so much movement in external rotation, the ballet dancer may create too much elasticity in the tonus of the adductors. In isolated exercises, such as use of the Pilates Magic Circle,2 these adductor muscles may appear strong; however, this doesn’t necessarily mean that this strength will carry over to the more complexly coordinated movements while dancing. Classical ballet coordination is external-rotation-centered; in fact, a typical dancer’s perception may be that external rotation is the most important priority. In training dancers, George Balanchine [1904-1983] is said to have focused on a consistent use of 180° turnout in more positions than ever before. The body image of the ballet dancer is built on a strong appearance and use of turnout. This is why many of them are said to “walk like a duck” in their pedestrian life. Certainly, there is muscular imbalance created and coordinative patterns set; however, there is also a self-identity perceptual basis for the walk, often seen in dancers around Lincoln Center in New York City.

Darwinism and ballet dancers meet on the topic of turnout. Ideally, yet a rare occurrence, 90° of turnout is achieved by approximately 60°-70° external rotation at the hip joint, about 5° coming from the natural inclination of the knee, and the remaining amount at the ankle and foot. Factors that determine a dancer’s ease in external rotation at the hip are: the angle of femoral neck anteversion (FNA), the shape and orientation of the acetabulum, and the elasticity of the ilio-femoral ligament and soft-tissue structures that cross the hip joint. Dancers who have a poor turnout due to increased FNA, an anteriorly oriented acetabulum, or inelasticity of soft tissues may ‘cheat’ by attempting to make up the difference in the knee or ankle. These maladaptive strategies lead to abnormal forces, causing injuries such as medial meniscus tears or hallux valgus. Nothing is worse than seeing a young dancer place his/ her feet in the ideal 180° turnout and then make the hip, knee, and ankle accommodate (see Figure 2). Eventually, one or more of these structures will suffer – often ending a dream or career. This understanding is critical in training young dancers. Even if a dancer has ideal external rotation at the hip, Hubert makes the point that turnout is an action that must be coached through the whole body, with responsive shifts in gravity centers. Too often, it is coached as an isolated action of the hip socket – such as through endless ronds de jambe [circular motion of the leg originating at the hip socket] without whole-body embodiment of the action. Rolfers can do important structural and functional work with turnout; however, the first step is to determine the dancer’s natural turnout without decompensatory mechanisms to achieve an idealized turnout.

Idealized 180° turnout is part of a prescribed classical ballet aesthetic called ligne [line]. Ligne is the visual outline that a dancer presents when executing steps and poses and is seen as either good or bad. Some characteristics of good line are: 180° turnout, extreme-range plantar flexion, and length in body parts, all of which are easier to achieve if one is born with the ideal structure. Ballet is often coached from a visual perspective, based on idealized ligne, so there is inherent incentive to use maladaptive strategies and often injury is the result.

Figure 2: Forcing 180º turnout often results in medial collapse of the midfoot.

AI: You mention Pilates. Many dancers are cross-training in approaches like Pilates and Gyrotonic®. Do you think these practices enhance technical abilities?

RC: The benefit in Pilates training comes when the dancer focuses on strengthening the whole coordination, not just the specific muscles involved. Isolated exercises are limited in use if the coordination is not made relevant to how the dancer executes the movement in real time relational to the environment, including gravity. If the ballerina does not have strong enough medial line activation, she may not have enough coordinative tonus in her adductors to counterbalance the power of her outward hip rotators, so her weight will transmit laterally down her leg, causing her to slightly sickle her foot while en pointe. Over time, this may displace the talus laterally straining the lateral ankle ligaments and putting the knee and hip at risk. It can also displace the first metatarsal, leading to bunions and other injuries. The field of dance medicine often considers each of these injuries as separate events, not as a whole pattern relating to gravity. A ballerina must have clarity and strength in the relationship of the center of gravity in her pelvis to be right over her pointes, because with that much force and velocity, even a small displacement over time can cause movement and structural problems. Rolfers are somewhat unique in considering actual pathways of weight transmission through the body, as related to gravity, on an individual basis. In other words, just because the pointe shoe is designed for weight to be transmitted through the center of the talus to the first metatarsophalangeal joint doesn’t necessarily mean that each dancer coordinates her pattern of arriving en pointe that way.

Additionally, in turnout, the functional midline of the leg moves posterior, falling more on the semimembranosus/adductor line. This means that strength in the coordination of the calcaneus-to-ischial tuberosity connection is essential. A dancer has two functional midlines: the dancing one and the pedestrian one. In working with any dancer who uses turnout, I try to cultivate a felt sense of both midlines and, more importantly, an option to return to a more ‘natural’ stance and gait in pedestrian life. This is important as a restorative activity in counterbalance to the demands of classical ballet. According to Hubert, there is a functional repetitive stress injury of constant turnout because, over time, the external hip rotators will become increasingly more tonic, instead of phasic, causing a loss of potency in their activation and resiliency. When the coordination of dance turnout is constantly used in daily activities, the cumulative strain will eventually go beyond soft-tissue spasm and adhesion to mechanical fatigue, and turnout – the most fundamental action in classical ballet – will become ineffective. To restore phasic action potential in the external rotators, one must not only rehabilitate structural trauma but also restore coordinative integrity.

AI: So you frequently work to balance the medial and lateral lines, both structurally and functionally in terms of body maps, to support ballet dancers in their pointe shoes. Do you ever work with the actual foot in the pointe shoe?

RC: Pointe shoes are primarily designed for dancing en pointe. In working with a ballerina, one must consider the pointe shoe to be an extension of her leg. It is part of her peri-personal space and allows the action potential for balancing in full plantar flexion (Figure 3). So, in a sense, the Rolfer needs to include the pointe shoe in the Rolfing session. When the practitioner perceives the pointe shoe in this way, without the overlay of the shoes being wrong, harmful, or unnatural, more productive work can be done.

Figure 3: Wilfride Piollet in Swan Lake at l’Opéra de Paris, 1977.

The pointe shoe, importantly, is also the conduit through which the ballerina relates to the ground. In modern ballets, the ballerina is often required to transition from demi-plié [turned-out position with knees bent and heels on the ground] through demi-pointe to full pointe many times. Balanchine influenced a shift away from the ‘pop up’ to full pointe to include the roll up to full pointe through demi-pointe, necessitating more foot strength and changing the factors necessary for efficient coordination. Because the pointe shoe is designed for end-range plantar flexion and the platform [or sole] is a bit rigid and unstable, injuries often happen when the ballerina lands a jump in demi-plié and then transitions to full pointe – all performed in turnout. A dancer is especially injury prone if her coordination for turnout includes gaining extra degrees by forcing rotation at the knee or ankle – sickling – resulting in over-pronation of the midfoot.3 This results in poor biomechanics and will leave her without power for the propulsive action required to arrive with stability en pointe.

One might consider that similar mechanics apply whether one is dancing in pointe shoes or walking in sneakers. Attention to the action and timing of the transition from landing to full pointe is essential, just like the importance of the transition from the landing phase to propulsion phase is key in pedestrian walking. Often foot and ankle biomechanics are explained as isolated joint actions, mostly centered on the triplane action of the subtalar joint. While biomechanical actions are essential to understand and restore, they do not provide adequate consideration of the functional coordination of the foot while dancing or walking without inclusion of the mover’s relationship to gravity, shifting body weight, and the nature of the ground, including variances in the quality of the terrain and its reaction forces. It is the foot’s response to the ground and shifting body weight that creates the joint motion, not the other way around.

AI: I know that there are many, but can you describe three essential foot biomechanical actions to consider when treating a dancer?

RC: Let’s see, three key functional relationships that come to mind are:

Of course, all are important, but given the demands of dance training, these three are essential to support and adaptability. They are essential to pedestrians too.

AI: Can you describe how you might work with a ballet dancer’s foot to train the transition across the transverse arch?

RC: Yes, transition across the transverse arch and propulsive toe-off was a key point in many of Hubert’s workshops, and it is critical for any type of dancer – whether full pointe, demi-pointe, or no pointe. In fact, it is important to any person, dancer or not. I have worked with it by using an artificial floor in my practice. You can create an artificial floor by moving your table to the wall so clients can lie on the table and contact the wall with their feet, or you can use a book or other flat surface to create a floor. Some practitioners are lucky enough to have tables with artificial floors attached. The Pilates Reformer is also useful.4 Whatever approach you use to create the ground, the key point is waking up the client’s ability to actually sense through the feet – to stimulate the proprioceptors. As humans, we are less inclined to authentically touch with our feet. Instead, we tend to make contact and then plant, brace, or prop instead of maintaining an alive touching and listening relationship with the ground. Aliveness in our felt sensitivity provides food for the nervous system and informs movement centers in our brain about necessary nuances in balance and movement. You can imagine how useful this is for any kind of dancer. By working with tracking and timing across the transverse arch to initiate a push-off or a balance on top of the first metatarsal, you can educate the foot toward more integrity in movement.

With ballerinas, I do this work both while they are barefoot and wearing pointe shoes. With tango dancers, I have them wear their four-inch heels. Any time shoes limit or define one’s ability to contact and feel the ground, the ankle is vulnerable, so maximizing the aliveness of the available contact is important. Proprioceptors in our feet and ankles communicate to our brain, and along with our vestibular system and peripheral vision they tell us where we are in space.

AI: What about space? Relationship to space is such an important concept in Rolfing SI and Rolf Movement and is also central in dance training and performance.

RC: Space is another essential topic to address with dancers. Hubert made a tremendous contribution to the field of Rolf Movement by clarifying the importance of an upper gravity center (G’) for head, arms, and chest. Located in the thorax and relational to the space around us, G’ is relevant to G, the center of gravity of the whole body located in the pelvis and relational to the ground.5 Important to dancers is the understanding that the biomechanics of the hip and pelvis will change, including the rotation of the femurs, depending on the anterior/ posterior placement of G’ referenced to the horizontal axis of the femurs. G is referenced to its vertical projection on the feet, specifically the transverse tarsal joint (or Chopart’s joint). Having fluidity in the functional relationship of G and G’ allows for greater range-of-movement expression and efficiency with gravity. Session one of the Rolfing SI series begins this process.

As movers, we may have a natural affinity toward initiating movement from either our sense of space or ground. I never get tired of watching the clip of Gene Kelly and Fred Astaire (see still image in Figure 4, video viewable at http://tinyurl.com/fred-gene) dancing the same choreography together. Hubert introduced this clip to us many years ago to show the variation between a dancer who initiates movement by relating to the ground, like Kelly, and one who initiates by relating to the space around him, like Astaire. Of course, they both have an easy connection with both ground and space.

Figure 4: Fred Astaire (left) and Gene Kelly (right) in Ziegfeld Follies, 1945, MGM. Photo: mptvimages.com.

However, at the moment of initiation, Kelly pushes into the ground and Astaire reaches into space. I love seeing this because it makes one’s innate gravitational relationship to ground and space so clearly visible and real. One might call this the way that Kelly and Astaire find resource at the moment of initiation – or what we call in Rolf Movement the ‘pre-movement’. So working with dancers to help them identify their innate preference for ground or space initiation may be helpful, especially because dance choreography often demands adaptability in working with both ground and space movement orientation. Knowing one’s preference for initiation can facilitate clarity.

AI: You mentioned earlier that ballet has always favored a light, ethereal quality, which would lend itself to a more spatially oriented approach. How do ballerinas embody space differently than, say, modern or hip hop dancers?

RC: For a ballerina, a developed sense of spatial support is essential because this is what creates that weightless, floating feeling, and most of the classical ballet vocabulary depends on it for refined execution. Also, from a practical sense, this is what allows the ballerina to not experience so much weight bearing down on her toes when en pointe – she is literally supported by the space around her. When a ballerina gestures or even looks at the ground, it appears to be very far away from where she lives. One can look up various professional ballet companies’ Odette or Odile solos from Swan Lake on YouTube and easily see examples of this upward embodiment of space. Even when she kneels, her knee makes the long journey to the ground from above. On the other hand, when one watches the opening movement in Le Sacre du Printemps choreographed by Pina Bausch, also available on YouTube, one has very little sense of the space – it is the dancers’ relationship with the ground that is primary and compelling as they stomp to the driving rhythm of Stravinsky.

Modern dance technique and performance often rely on a strong relationship with the ground as the basis for movement, and often the themes of modern dances revolve around earthly emotions and states, as opposed to the more ethereal ballet themes. Hip hop dance certainly uses the ground as the basis for supplying the rhythm – the whole body expresses timing and rhythm because of the dancer’s physical exchange with the ground. Often, it feels as if the ground is dancing too. One can view an example of this in any Rennie Harris Puremovement video. In order for Savion Glover, a tap dancer, to tap extraordinarily complex rhythms, he is almost suspended energetically from the sky, so that his ankles and feet have the freedom to relate rhythmically to the ground. This is similar to the style of the Danish choreographer August Bournonville, who choreographed very quick, light, and meticulous footwork. In order to achieve the desired speed and lightness, the dancers must relate to the ground from the top down, not from the ground up. How we initiate movement and how we relate to the world around us manifests in coordinative patterns that shape our structure. For many years, Hubert has articulated the importance of addressing the structural, coordinative, and perceptual aspects of human function with relevance to gravity.

AI: More and more, ballet companies are incorporating modern choreography into their repertory, and modern performance artists like Kyle Abraham draw upon hip hop, modern, and classical ballet, so the boundaries between dance forms are perhaps becoming more fluid.

RCYes, this requires even more adaptability from the dancer. When a dancer comes in with difficulty performing a technical movement or a choreographic one, a valuable place to begin is to clarify what is being asked in terms of ground and space. Often dancers, like any of us when having a physical difficulty, want to blame it on something inside [the] body: “It’s because my sacroiliac joint (SI) is unstable,” “It’s because I have a scoliosis,” and so forth. There may be truth in these concerns, but by also considering embodiment relating to ground and space, we are engaging in a more holistic intervention that may actually solve the biomechanical issue. As Rolfers, we certainly know that our relationship with gravity has everything to do with our movement potential, so why not bring that concept to the foreground in our work?

For the dancer who is having trouble with a leap, you might ask, “Are you focused on pushing the ground away or reaching into the space? Can you feel the sky above you at the apex?” To the dancer who is having difficulty with balance, you could ask, “Can you allow the support from the space to come meet you? Can you sense that the space is holding you up?” For the dancer who is unable to easily transition from standing to rolling, ask, “What happens if the ground comes up to caress you?” It’s about perception and the story that we are telling ourselves as we are moving. In a sense, we have to get out of our body images and abstractions so that we can become embodied in a sensory experience relevant to our present environment. After all, the experience of leaping is not the sum of the leap’s biomechanical parts. Dancers, like all of us, may have difficulty with a movement because of a structural lesion and/or because of a perceptual inhibition or misunderstanding that leads to faulty coordination. Helping a dancer make the connection between movement and elements of structure, coordination, and perception is very rewarding, especially when the dialogue incorporates gravity as the organizing principle. Once established, you can work with the particulars of the SI joint, scoliosis, or whatever the specifics more productively.

AI: What if a dancer comes to you wanting not to enhance technical performance but to rehabilitate from an injury? How can working with ground and space relationships help with rehabilitation?

RC: It’s absolutely a valuable method of intervention when a dancer is rehabilitating from an injury. Once the acute phase is over, it is essential to rebuild [his/her] sense of ground and spatial relationships. The tendency is to only focus on the injured part: “What is it doing? How does it feel?” “Oh, it feels bad today. Did I re-injure it?” One has to re-establish trust in the ground and felt support from the space so that the injury can truly disappear, instead of staying locked into the coordination of guarding or doubt. This happens through an embodied sense of one’s connections, both inside and outside the body. By over-focusing on the injury and not rebuilding the connections to the environment, the dancer’s body image remains fixed in ‘injury’, and as we know, that makes one prone to more injury.

AI: How else do you address body image, Rebecca?

RC: Helping dancers better match their body image to their actual body schema is another course of valuable Rolfing work. For instance, a dancer may not know where her hip socket is actually located.

When you ask her where the hip socket is, she may point to the outer hip – the area of the greater trochanter. This may be because her body image makes outward rotation a priority and the felt action is located where the external rotators insert – at the greater trochanter. However, her body map does not include the actual hip socket, the real site of rotation. Knowing and feeling exactly where one’s hip socket is located and how the head of the femur rotates helps reduce wear and tear on the hip. In a felt sense, the hip socket comes home, and movement will engage a more powerful and elastic sequence of muscle chains. Similarly, knowing what it means to have a horizontal ankle hinge, especially in turnout, will improve alignment. Without knowing much about dance, there are opportunities for a Rolfer to help clarify and fine-tune a dancer’s body image to more accurately align with the potential of her body schema, resulting in more ease, power, and efficiency in movement.

AI: You’ve worked with many dancers over the years and you’ve watched a lot of dance, so I’m curious to know what you think makes a dance performance exceptional. Why do some performances give us goose bumps while others don’t?

RC: As audience members, when we watch dance, we are moved when we can connect and feel. Some dancers evoke an intense emotional connection. Others evoke appreciation for their technical skills, but no feeling of connection. For me, one of the things that makes the difference between a moving performance and one that is just technically proficient is whether the dancer manages to capture the basic human movements that lie beneath the technique – such as jumping, leaping, skipping, running, punching, kicking, and throwing – without self-consciousness, like a child. The child is one with the puddle that he is leaping over – there is no technique, just puddle and leaping. I think that this ability is related to something Hubert has worked with called ‘foundational movements’. These are movements in our development that underlie more complex ones. For example, can you push someone away – a strong gesture of saying “no” – without pushing yourself? Can you embrace someone with a big gesture of saying “yes” without allowing fear or doubt to creep into your arms? Can you really run toward someone without hesitation about rejection? Can you easily throw something far away without.

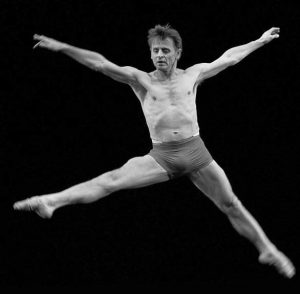

clutching? A leap is exciting when we can feel the slight recklessness beneath it. This quality comes from the ability to truly throw something away from us. I remember Hubert saying, “In order to leap, you first must be able to throw.” Humans respond to these qualities of movement in other humans, dancing or not. I think that when a dancer really captures the audience, like Mikhail Baryshnikov (Figure 5) does, it is because he/ she has maintained this human connection within all the technical proficiency.

Figure 5: Mikhail Baryshnikov, Barbican Theatre, London, 2004.

Photo: Gareth Gay/Alpha/Globe Photos.

Endnotes

Rebecca Carli holds BA and MFA degrees in dance and serves on the RISI faculty. She lives in the Washington, DC area, where she maintains an active practice in Rolfing SI and Rolf Movement Integration and teaches a variety of somatic movement courses.

Amy Iadarola is a Certified Advanced Rolfer practicing in the Washington, DC area. She is certified in Pilates and has twenty-five years’ experience in dance.Dancers and Rolfing® SI[:]

As you register, you allow [email protected] to send you emails with information

The language of this site is in English, but you can navigate through the pages using the Google Translate. Just select the flag of the language you want to browse. Automatic translation may contain errors, so if you prefer, go back to the original language, English.

Developed with

To have full access to the content of this article you need to be registered on the site. Sign up or Register.